|

The Tri-State Water War

The issue

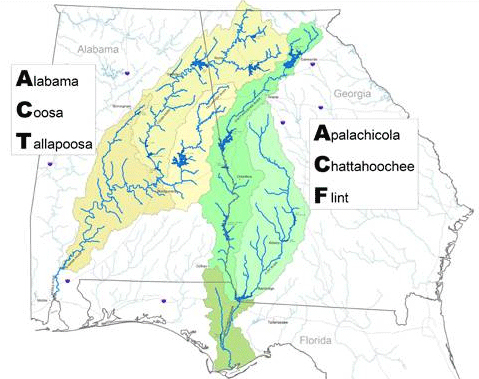

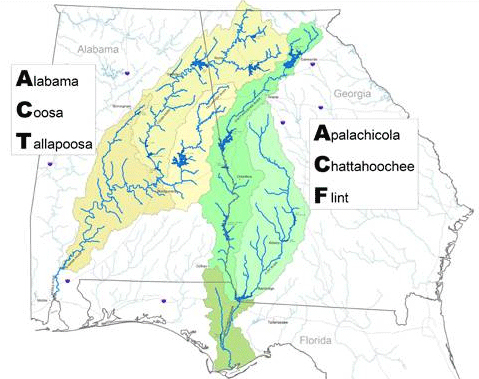

For more than three decades, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida have disputed the use of two shared river basins—the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) and the Alabama-Coosa-Tallapoosa (ACT). These river systems are used to meet multiple needs, including drinking water, power generation, agriculture, aquaculture, navigation and recreation.

With its population nearing 6.1 million people, metro Atlanta is the country’s third-fastest-growing city. Atlanta’s Fulton County is expected to need more than 300 million gallons of water per day by 2035. The city is dependent on surface water, which makes it extra sensitive to drought. The city currently gets 70 percent of its water from Lake Lanier, which lies about 50 miles to the northeast. The lake was created in the 1950s when the Buford Dam was built to wall off a section of the Chattahoochee River. The Chattahoochee River Basin extends across all three states, and any further usage restrictions on the basin would add fuel to the “tri-state water wars,” a term describing the two decades of legal battles over the Chattahoochee, Flint, and Apalachicola rivers.

Timeline

Since the 1990s, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida have fought over the use of water in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin (ACF), which is heavily influenced by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ operation of Lake Lanier’s Buford Dam and four other similar dams. Lake Lanier lies within the Chattahoochee’s headwaters, just north of Atlanta.

The Corps built Lake Lanier in the 1950s with clear Congressional authorization for flood control, navigation, and hydropower. Over time, however, Lake Lanier has become the primary source of drinking water supply for metro Atlanta, and Alabama and Florida have argued that Georgia withdraws too much and isn’t sharing the water fairly. All three states have turned to the courts to try to resolve the conflict. Key litigation and policy decision milestones include:

- In 2009, a federal district court judge ruled against Georgia, deciding that water supply was not an authorized purpose of Lake Lanier. The judge gave Georgia three years to reach a water-sharing agreement with Alabama and Florida and to get Congressional approval.

- In 2011, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the 2009 district court decision, ruling that water supply is an authorized purpose of Lake Lanier, on par with hydropower, navigation, and flood control. Furthermore, the appeals court gave the Corps one year to determine the extent to which it could operate Lake Lanier to meet water supply needs in addition to the other authorized purposes.

- In 2012, the Corps responded to the 2011 Eleventh Circuit decision, determining it has discretion to operate Lake Lanier in order to meet Georgia’s current and future water demands.

- In 2013, Florida filed an original jurisdiction action against Georgia in the U.S. Supreme Court, alleging that Georgia’s unreasonable use of water in the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers had impacted the Apalachicola River, damaged the oyster ecosystem, and harmed Florida’s economy. This was the beginning of Florida v. Georgia (no. 142).

- In 2017, the Corps released an updated ACF Water Control Manual to guide operations of the Corps’ five reservoirs, dams and navigation locks in the basin to meet Congressionally authorized purposes of power generation, flood control, navigation, water supply, recreation and fish and wildlife. This manual had not been updated since 1958.

- In 2017, the State of Alabama and the National Wildlife Federation et. al. filed separate legal challenges against the Corps, alleging that the Corps did not follow National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) procedures when revising the Water Control Manual.

- In January 2021, the state of Georgia and the Corps finalized a $70 million perpetual contract for access to storage space in Lake Lanier – or a bucket in a bucket – for 254,170 acre feet and up to 222 million gallons of water per day. This contract does not guarantee that the water will be there, just that the state has access to storage space. Georgia will develop individual sub-contracts with Lake Lanier’s five water utilities. It is worth noting that the contract is based on now outdated and inflated need and population projections through 2050. This means there may actually be enough water to meet demand well past 2050, and thus the now abandoned Glades Reservoir is unlikely to get built in the future.

- In April 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a final opinion in the Florida v. Georgia legal case that began in 2013, in which Florida claimed Georgia unreasonably overconsumed Chattahoochee and Flint River water to the detriment of the Apalachicola downstream. In plain terms, the court dismissed Florida’s claims. In a 9-0 opinion, the court determined that Florida failed to make a compelling legal argument and failed to provide sufficient evidence that Georgia uses too much water or that any harm to Florida’s oyster population could be traced to water use in Georgia. You can read the opinion here.

- In August 2021, a federal judge rejected the lawsuit lodged by Alabama, and the National Wildlife Federation et. al. claiming that the Corps did not follow administrative procedure or fully comply with other environmental laws when preparing the Water Control Manual that governs the operations of Buford Dam/Lake Lanier, West Point Dam/Lake and the three other federal dams in the ACF. Alabama has appealed the decision.

- In August 2021, the Corps made a decision with repercussions for Lake Lanier and the Chattahoochee River. The Corps approved a new water supply accounting

Source: Chattahoochee Riverkeeper

Dispute spills over into Tennessee

Adapted from the NRDC

In 1818, a government surveyor named James Carmack bumbled Tennessee’s southern border. Instead of drawing a line along the 35th parallel, as designated by Congress, he put the border a mile south, in Georgia. The blunder kicked off a conflict that has spanned two centuries, with many in the Peach State wanting to reclaim the land—and especially the freshwater that comes with it.

Between 2017 and 2019, the Georgia General Assembly passed two resolutions to negotiate the 51-mile-long “true border” with Tennessee. What Georgia’s lawmakers really want is a pipeline into the Tennessee River, which runs through Chattanooga north of the border before dipping down into Alabama, narrowly missing Georgia (at least according to Carmack’s survey). The most recent resolution argued that since some of the river’s tributaries originate in six Georgia counties, the water is being stolen.

Tennessee has never taken seriously Georgia’s requests to negotiate. In 2008, to mock (or perhaps to fuel) the ongoing discord, Chattanooga’s mayor sent a truckload of bottled water to Atlanta instead of showing up at the bargaining table. In fact, the Volunteer State has punted on the issue since 1887, while Georgia’s legislature has voted to reopen negotiations dozens of times. Some consider the recent proposal to build a 130-mile pipeline—which would have to run over Georgia’s Lookout Mountain pipeline before stretching to Atlanta—a logistical nightmare that would cost tens of millions of dollars.

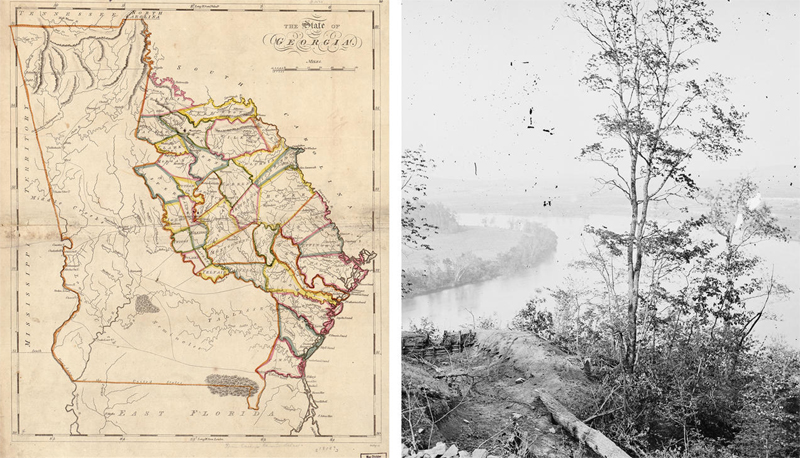

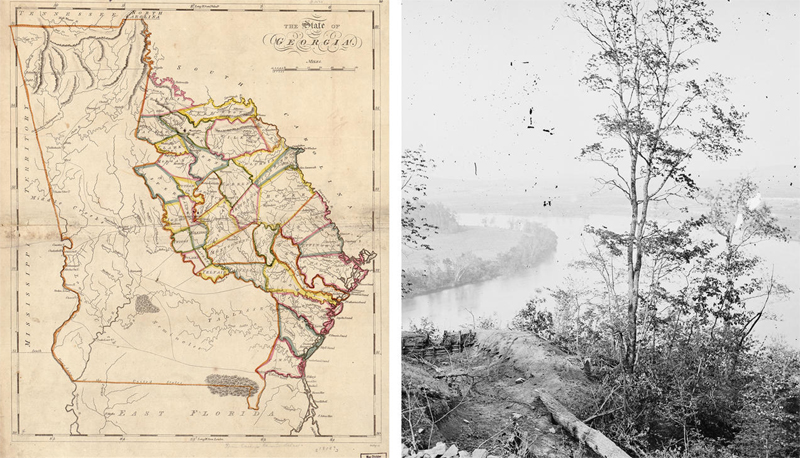

From left: An 1818 map shows the Georgia Tennessee border drawn along the 35th parallel; a view of the Tennessee River from Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga

Library of Congress

“If we collected one-third of the water that flows out of Georgia and into the Tennessee River, it would solve the water wars,” says House of Representative, Republican Marc Morris. He estimates that with a pipeline into Tennessee, his state could recapture 500 million gallons of water a day for its residents. Morris says the only other solution would be to build a desalination plant on the Atlantic coast and pump its output some 250 miles northwest to Atlanta. But that, he says, would produce “the most expensive gallon of water” Georgia has ever seen.

CRK has always advocated for what is best for the river and the people who depend upon it, regardless of political or jurisdictional winners and losers in the water wars.

For its part, the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper believes Alabama, Florida, and Georgia must negotiate an interstate compact to equitably divide the waters. Furthermore, climate challenges – not legal challenges – should drive collaboration and equitable water management decisions.

|

|

All rights reserved 2026 - WTGA - This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part and may not be distributed,

publicly performed, proxy cached or otherwise used, except with express permission.

|

|